Today is International Women’s Day, an annual event to celebrate women’s achievements and promote women’s rights. This year, I have highlighted four French women musicians, since music is close to my heart. They achieved remarkable things, sometimes against considerable odds, transcending the gender and racial restrictions of their eras.

Pauline Viardot (née Garcia; 1821-1910)

Pauline Viardot was the daughter of musicians. She was destined to be a pianist and studied under Franz Liszt, giving her first recital at the age of 16. However, her elder sister Maria, a cantatrice, died in a riding accident, and their parents decided that Pauline should take her place. In 1839, she made her opera debut in London as Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello.

In 1840, she married Louis Viardot, a theatre director and critic. Remarkably, he resigned from his post to manage his wife’s career as an operatic mezzo-soprano.

The range of Viardot’s voice and her acting skills assured her success, but in 1863, her voice gave out. She turned to composing songs for her singing pupils, meriting a backhand compliment from Liszt: “At last the world has found a woman composer of genius.” She also wrote operas and operettas. Her opera Cendrillon (Cinderella) was staged when Viardot was 84.

Despite the enforced change of direction after Maria’s death, Viardot was her own woman. She forged relationships with other musicians, composers and writers and determinedly pursued her career while running a family of four children.

Emma Calvé (1858-1942)

Few people have heard of Emma Calvé today, but she was one of the brightest singing stars of Belle Epoque France. I have a soft spot for Calvé, partly because of her rags-to-riches story, and partly because she was born in Aveyron.

Calvé showed exceptional early ability as a singer, and the Bishop of Rodez, captivated by her voice, declared that she should have a professional career. However, money was short after her parents separated, and Calvé moved to Paris with her mother and brother. She found a singing tutor, who secured serious singing engagements for her.

Calvé’s stage debut was as Margeurite in Gounod’s Faust in Brussels in 1881. Her career took off when the Opera-Comique in Paris engaged her. She travelled the world, delighting audiences with her performance in Bizet’s Carmen, which she sang more than 1,000 times.

Calvé led an extravagant and colourful lifestyle, buying a château in Aveyron and marrying a philandering and debt-ridden Italian tenor, who was 17 years her junior, in 1911. She gave up singing opera in 1904 but continued to give recitals. During World War I, she raised money for the French war effort, singing to rapturous audiences in America.

Later in life, Calvé became increasingly fascinated by the occult and the paranormal. She died in relative poverty in 1942, having sold her château some years before.

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

Lili Boulanger was a composer and the younger sister of the eminent music teacher, conductor and composer, Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979).

I also have a soft spot for Lili Boulanger. Having struggled against chronic illness all her life, she died tragically young at the age of 24. The Boulanger parents were musicians (her mother was a Russian princess who married her Conservatoire tutor) who nurtured their daughters’ musical talents.

Boulanger was a musical prodigy, who learned singing as well as the piano, violin, cello and harp. She later learned harmony and composition at the Paris Conservatoire. At 19, Boulanger became the first woman to win the prestigious Prix de Rome for her cantata Faust et Hélène.

World War I and the solitude of her illness greatly affected Boulanger, and this is reflected in her haunting melodies, which she wrote mainly for voice. One of her last works, the Pie Jesu for soprano, string quartet, organ and harp, is almost a requiem for herself. I had the great privilege to sing this piece, adapted for organ accompaniment, once in a concert.

What might Boulanger have become if it hadn’t been for her untimely death?

Josephine Baker (1906-1975)

Josephine Baker was born in St Louis, Missouri, but took French citizenship later on. Her early life was marked by poverty, a turbulent family life and witnessing racial violence.

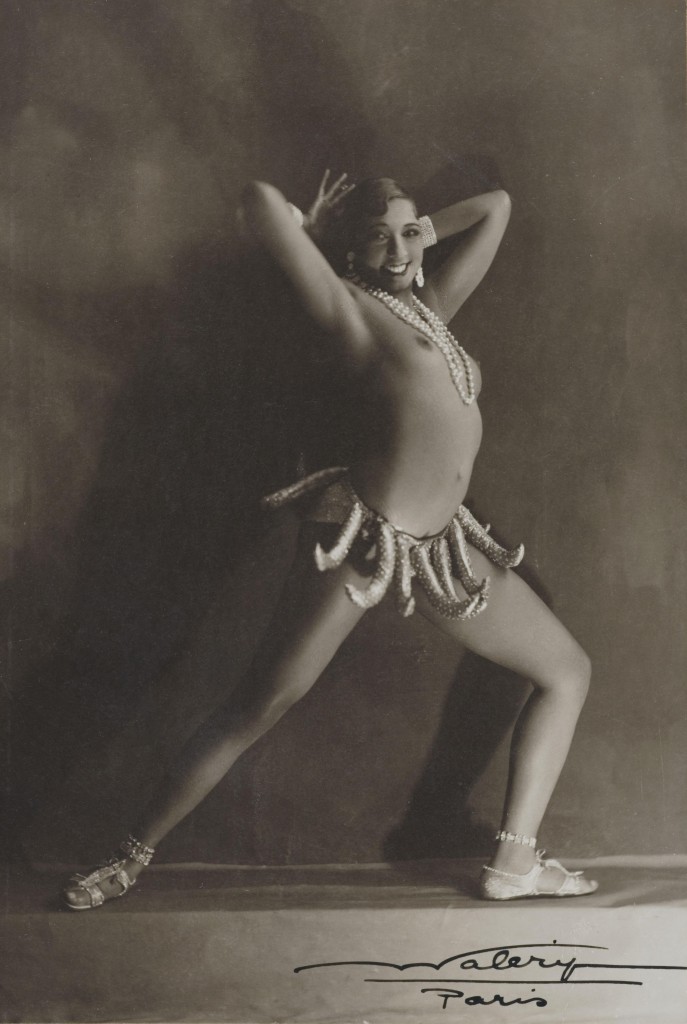

Baker joined a travelling theatre group when she was fifteen. She graduated to a chorus line and became popular with audiences for her personality and humour. She and her second husband divorced in 1925, and she moved to Paris. Baker’s erotic dancing, risqué songs and flamboyant costumes were a hit with the audiences of les Années Folles (the Roaring Twenties), and she found the artistic and personal freedom in Europe that she lacked in America.

Lucien Waléry, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Before the German occupation of France in 1940, Baker performed for and socialised with the German military, using her celebrity to obtain secret information for French military intelligence. After the occupation, she moved to her château in the Dordogne, where she helped Resistance efforts.

As a performer, Baker could travel to neutral countries more freely. She wrote notes about German troop movements and installations in invisible ink on her sheet music and pinned notes inside her underwear, assuming that her fame would spare her strip-searches.

Later, she was a civil rights activist and refused to perform to segregated audiences in the States. After Martin Luther King’s assassination, his widow asked if Baker would lead the Civil Rights Movement, but she refused for her adopted children’s sake.

Baker continued to perform until shortly before her death. In November 2021, she became the first Black woman to be inducted into the Panthéon in Paris, where the great and the good of France lie. Her body remains in Monaco, her last home.

Each of these women is worthy of far more space than I can devote to them in a blog post.

You might also like these posts:

Copyright © Life on La Lune 2024. All rights reserved.

Hi Vanessa. I love hearing about women spies! It’s also humbling to think how they put themselves at risk for their country – not a choice I have ever had to make……yet anyway.

MJ

LikeLike

Josephine Baker was a remarkable woman and extraordinarily courageous.

LikeLike

I must confess I had only heard of Josephine Baker, so I must thank you for introducing me to the three other worthy women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s a pity the other three are not better known, especially as they were celebrated in their lifetimes. Emma Calvé in particular was a superstar.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating information on your blog as always. Although within striking distance of us we haven’t visited Josephine Baker’s chateau in Dordogne although some of our visitors have. But a couple of years ago we went to an exhibition dedicated to her life and work in Souillac which was very interesting due to the range of exhibits giving glimpses of an amazing woman.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We haven’t visited her château, either, although I think it featured in one of the Martin Walker Bruno books! She was certainly an amazing character, when you consider the unpromising start to her life. She really pushed the boundaries.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A quartet of amazing ladies

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love that – quartet! Very musical. They were indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person