You’ve no doubt heard of the pioneering aviators Charles Lindbergh and Louis Blériot. But have you heard of Dieudonné Costes? In his day, he was equally famous, and he set a number of records for distance flying.

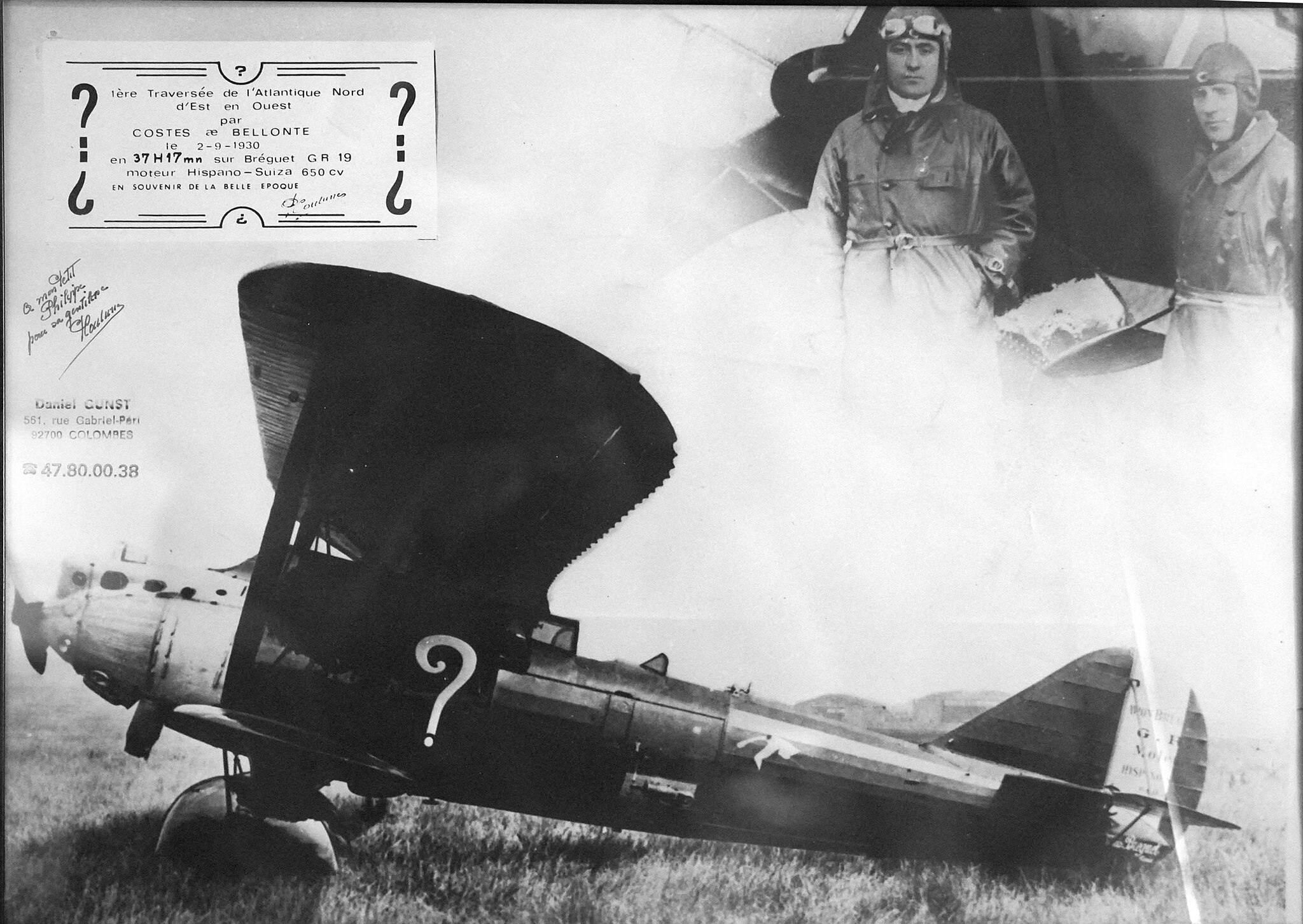

Costes’ most notable exploit was to become the first to cross the North Atlantic nonstop from East to West, against the prevailing winds, in September 1930. He and his co-pilot, Maurice Bellonte, did it in 37 hours 18 minutes.

Budding interest in aviation

What I know about aviation wouldn’t fill a postage stamp, but Costes was a local boy, hence my interest. He was born in Septfonds in 1892 to parents who worked in straw hat manufacturing, Septfonds’ main industry. The museum in Septfonds, La Mounière, ran a guided visit last weekend, focusing on Costes. This was a fascinating insight into the early aviators.

It’s hard to know why Costes nurtured such a thirst for adventure. His parents were unassuming middle-class people who had probably never travelled far themselves. He received a standard education, and a teacher described him as “more intelligent than studious”, but he developed a passionate interest in aviation. His parents financed his studies for a pilot’s licence. His obsession eventually took him a long way from Septfonds.

Costes joined the army hoping to become a military pilot but was initially assigned to mechanic’s duties during World War I. However, he persisted and went to the Eastern Front in the Balkans, where he became a flying ace, credited with six “kills”. After the war, Costes worked as a pilot for several civil aviation and manufacturing companies.

Daring exploits

The 1920s were a period of increasingly daring aviation exploits. Costes had already broken several world distance records when Lindbergh made his epic eastbound solo flight across the Atlantic in May 1927. Costes was determined to do the same in the opposite direction. He and Bellonte tried in July 1929, but bad weather forced them to turn back.

Finally, in September 1930, all the signals turned green. The guide at La Mounière described Costes’ meticulous preparations. She showed us his flying suit, boots and gloves. Since they would be flying in open cockpits, the men needed warm but supple clothing.

Le Point d’Interrogation

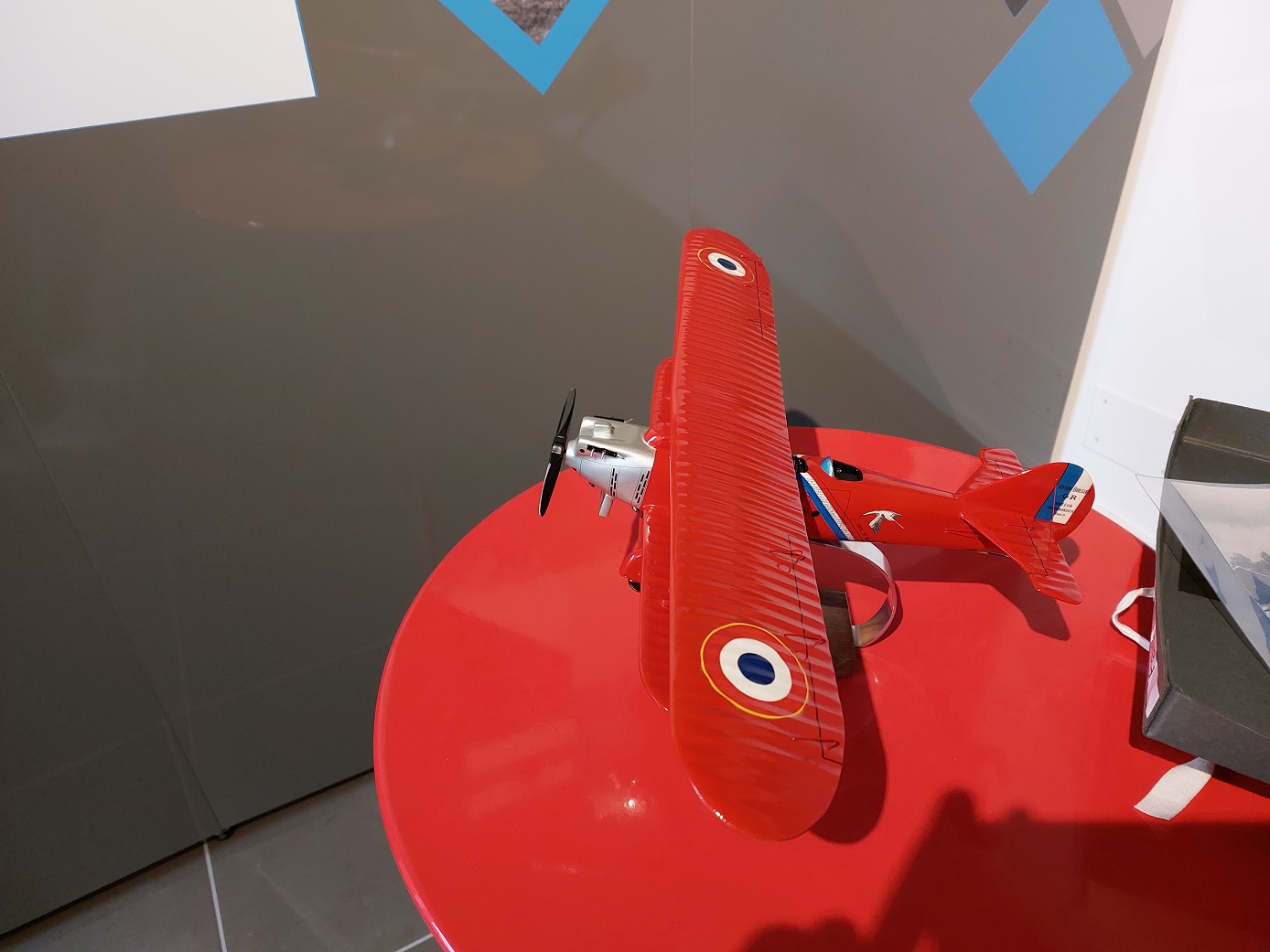

Mystery shrouded the financing of Costes’ plane, which was a Breguet XIX specially adapted for long-distance flights. A journalist’s remark about the secrecy around it inspired Costes to name his plane ‘Le Point d’Interrogation’, and he had a white question mark painted on the side.

In fact, the wealthy perfume manufacturer, François Coty, bankrolled Costes’ attempt, but withheld his name until the duo had landed. Others had tried before Costes and failed.

On the morning of 1st September 1930, Costes and Bellonte took off from Le Bourget airfield in front of a large crowd. As they disappeared over the horizon and the whirring of the engine faded away, many must have wondered if they would make it.

Televersement et modifications : G.Garitan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

To us, transatlantic flights are commonplace. We travel in relative comfort for six to eight hours. Costes and Bellonte flew in open cockpits in a prop-driven biplane, barely more sophisticated than a period car, navigating with maps and compasses. The men were unable to move for 37 hours and had to face whatever rain, wind or even ice the weather threw at them. They had provisions, but little space for excess baggage. And they were on their own with slim hopes of rescue if the plane came down.

The fatigue and boredom must have been overwhelming, but the adrenalin and constant apprehension about what might go wrong kept them going.

We watched a contemporary film of the plane’s take-off and its landing at Curtiss Field in New York. They carried 5,600 litres of fuel and arrived with less than 400 litres to spare. A cheering crowd swarmed around the bright red plane as it rolled to a halt, ignoring the policeman who tried to restrain them, and the two men clambered out.

KSAK:s tidning Flygrevyn, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

They were immediately hoisted onto enthusiastic shoulders.

New York treated the aviators to a ticker-tape parade. President Coolidge received them at the White House before they embarked on a victory tour of America in the Point d’Interrogation. On their return to France, they received a heroes’ welcome. Président Doumergue awarded Costes the Légion d’Honneur.

Domaine public – Photo d’auteur inconnu publiée en 1930., CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

After the Atlantic

Costes continued to fly, but this was his greatest exploit. During World War II, he worked as a double agent in the States with the FBI’s knowledge, passing aviation information of no value to the Germans. After the war, he was arrested and tried for collaboration but was cleared. However, the accusations must have tarnished his reputation.

In his later years, Costes developed a ski resort in Le Mont-Dore, Puy-de-Dôme. Misfortune struck again when seven people died in a cable car accident in 1965. In 1972, following a long court case, Costes’ company was judged largely responsible. By this time, he was in poor health. He died in May 1973, four months after a leg amputation.

What impelled these men? Monetary gain and glory certainly attended on success, but they can’t have been the only factors. Another, modern film celebrated Costes’ flight. I don’t know if these are his actual words, but they offer a plausible explanation: “I don’t do it to push the plane to its limits, but to push my own.”

Useful links

Follow this YouTube link to see the plane taking off from Paris and landing in New York.

Costes’ and Bellonte’s Point d’Interrogation is on display at the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace at Le Bourget.

You might also like these posts:

Copyright © Life on La Lune 2024. All rights reserved.